‘Everything depends on what we are and, in the diversity of time, how those who come after us perceive the world will depend on how intensely we have imagined it, that is, on how intensely we, fantasy and flesh made one, have truly been it. … We are all novelists and we narrate what we see because, like everything else, seeing is a complex matter.’

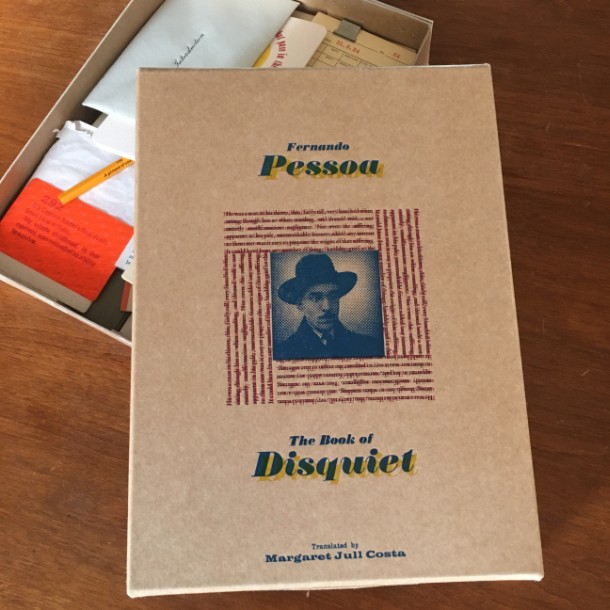

Sometimes it requires many more people than the author to make a book. Take the Serpent’s Tail edition of Fernando Pessoa’s The book of disquiet. It’s a version of the text edited by Maria José de Lancastre and translated from the original Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa. Three earlier Pessoa scholars undertook the original work of deciphering the handwritten notebooks and scraps of paper from which the text was derived and put into some sort of order. Then there’s the infrastructure a publisher requires to put a book in the line of sight of potential readers – the commissioning and copy editors, the marketing and administrative staff, not to mention those responsible for its look and feel, like the graphic designer. And (assuming we are not talking about a solely virtual edition) let’s not forget the printer, who brings the book into physical being. It’s not often that we think of these last two roles as having an equivalence to the intellectual effort of editor or translator. But with the Half Pint Press’ boxed, letterpress edition of The book of disquiet, I think it’s only fair that we elevate Tim Hopkins to the level of de Lancastre and Jull Costa, despite (knowing Tim) his inevitable protestations as we try to do so.

Pessoa began writing what has come to be known as The book of disquiet in 1912, and continued adding to it fragment by fragment until his death in 1935. Tim has spent very nearly as long bringing his singular vision and version of the text into being, printing a selection of the individual portions of Pessoa’s words on paper ephemera – a roll of bus tickets, a portion of a map, a menu, pages from a ledger, gift tags, raffle tickets, a playing card, a postage stamp – but also on a variety of other materials which can take ink – a photographic slide, a book of matches, a wooden tongue depressor, a drinks mat, pieces of cloth and jigsaw puzzle, and even along the sides of a pencil. It’s been a labour of love, in the truest sense, just as Pessoa’s writing of his texts was in the first place, seemingly without hope of them ever being published. This artful and soulful recreation of the trunk in which the fragments of writing that form The book of disquiet were found brings alive both the ordinariness of the imagined life lived by Bernardo Soares, and Pessoa’s extraordinary rendering of his interior. If you add to this the extensive ferreting about which has taken place to source materials in sufficient quantities; the sheer variety of those materials; the ingenuity with which the individual printing challenges have been met; and the bloody-minded determination to keep going, strike by laborious strike of the manual press – I am as in awe of it as I am of Pessoa’s sentences. And what Tim’s efforts inevitably lead us back to are those.

In one of the several hundred fragments of which The book of disquiet is comprised, Pessoa, writing in the guise of Soares, compares life to an inn in which he must stay until ‘the carriage from the abyss’ comes to pick him up. Soares says:

‘If what I leave written in the visitors’ book is one day read by others and entertains them on their journey, that’s fine. If no-one reads it or is entertained by it, that’s fine too.’

Any writer who is not widely read during the course of his or her lifetime might well need to think like this to be able to continue to believe in the effort of writing without a sense of the futility of that effort overwhelming and undoing them. But Pessoa’s subject was so often the futility of effort of any kind, and his writing about it so tenacious, that it becomes hard to believe it of him. Certain fragments towards the end of the Serpent’s Tail edition of The book of disquiet reveal that he was shrewd enough to guess that the trunk of texts and poems left behind when he finally caught the carriage to the abyss would sooner or later be discovered and disseminated. The visitors’ book was in fact a treasure chest of untold, unparalleled, gem-like literary fragments, and perhaps it was enough for Pessoa while he lived to know in both his heart, and in his astutely philosophical mind, that he was ahead of his time.

The translation by Margaret Jull Costa, one of at least four there have been into English, follows the thematic selection edited by Maria José de Lancastre, which while it promotes an element of repetition, makes the whole less random and unstructured. (Tim’s boxed version of the book reverses this process, which arguably makes it truer to what Pessoa had in mind himself: ‘I re-read some of the pages which, when put together, will make up my book of random impressions. And there rises from them, like a familiar smell, an arid sense of monotony.’) Themes – such as tedium, weariness, office life, solitude, dreams, love, writing – do recur and overlap, but there is more of a sense of accumulation than repetition as over the years Pessoa/Soares writes his way into and through these themes from ever-varying angles.

If you gauge a book by a desire to annotate the text or capture and save quotes from it, then The book of disquiet has few equals. When I read it, I find that the quotableness varies only according to my own receptivity and sensitivity. On a day when my mind has a greater or lesser number of cares which are distracting it, then Pessoa’s sentences can drift by me as light and free – or as insubstantial – as blown bubbles, evaporating with a silent pop almost before I’ve finished reading them. But on a day when I am, say, luxuriating in the bath, and the doors and windows of the inner apartment of my relaxed mind are fully open, then the words I read in my well-thumbed and wrinkled copy of The book of disquiet blow through that apartment like a freshening breeze, and I find myself wanting to capture between quote marks nearly every sentence he writes. Here are just a few of those:

‘Each of us is intoxicated by different things. There’s intoxication enough for me in just living. Drunk on feeling I drift but never stray. If it’s time to go back to work, I go to the office just like everyone else. If not, I go down to the river to stare at the waters, again just like everyone else. I’m just the same. But behind this sameness, I secretly scatter my personal firmament with stars and therein create my own infinity.’

‘Down the steps of my dreams and my weariness, descend from your unreality, descend and be my substitute for the world.’

‘One should abandon all duties, even those not demanded of us, reject all cosy hearths, even those that are not our own, live on what is vague and vestigial, amongst the extravagant purples of madness and the false lace of imagined majesties… To be something that does not feel the weight of the rain outside, or the pain of inner emptiness… To wander with no soul, no thoughts, just pure impersonal sensation, along winding mountain roads, through valleys hidden amongst steep hills, distant, absorbed, ill-fated… To lose oneself in landscapes like paintings. To be nothing in distance and in colours…’

‘The sentence was the only truth. Once the sentence was formed everything was done; the rest was the sand it always had been.’

‘I’m like a being from another existence who passes, endlessly curious, through this one to which I am in every way alien. A sheet of glass stands between it and me. I always try to keep that glass as clean as possible so I can examine this other existence without smudges or smears spoiling my view; but I choose to keep that glass between us.’

‘What is there in all this but myself? Ah, but in that and only that lies tedium. It’s the fact that in all this – sky, earth, world – there is never anything but myself!’

Sometimes when you read a fragment, it is true that you feel yourself succumbing to the same kind of tedium that Pessoa/Soares is describing – but then he hits you with a turn of phrase so beautifully crafted and so lucid in its perceptiveness that it leaves you as stunned as if the sun had suddenly penetrated a thick blanket of grey-white cloud.

I suspect many writers feel the way that Bernardo Soares feels. The difference may be that they are waiting with a greater or lesser degree of confidence for the torpor to pass, or for the muse to sing, and the story to emerge from the song; from what is initially a fog of shapeless forms within their minds. Pessoa remains or chooses to remain in that foggy state, and makes the tedium, torpor and solitariness the story. In so doing, ‘using my soul as ink’, he performs the alchemical transformation of which Soares believes himself incapable.

‘These pages are the doodles of my intellectual unconsciousness of myself,’ he writes. If so, why should we bother to be interested? Because the end results are not mere doodles, they are finely wrought and rendered fragments of Pessoa’s thought, passed through the medium of Soares, and sitting on top of a bed of submerged feelings and dreams. The fragments are ahead of time reports on the state of our twenty-first century minds and souls, full of acuity and insight about our atomisation and the relationship we have with our own selves. By some hundred years, and through his use of heteronyms, of which Bernardo Soares is but one of seventy or eighty Pessoa used during the course of his writing life, he anticipates the taking of multiple online identities in order to present facets of one’s self to the world. Perhaps inevitably this comes at a cost; from Soares himself, we hear the plaintive cry of someone within whom multiple personalities have run wild:

‘Who is this person I attend on? How many people am I? Who is me? What is this gap that exists between me and myself?’

Some writers – the best perhaps, though that’s not always recognised in their own time – are the advanced guard in terms of the evolution of how human beings think and feel. They report to us how they perceive the world, and allow those ways of perceiving to develop and take hold, until what once was strange and solitary becomes understood, a part of the collective consciousness. It pulls you up short when Pessoa himself addresses this notion directly. It’s as though he is present in the (bath)room with you in some ghostly way, beyond what has normally been the case as you read him:

‘One day, perhaps, they will understand that I carried out, as did no other, my inborn duty as interpreter of one particular period of our century; and when they do, they will write that I was misunderstood in my own time; they will write that, sadly, I lived surrounded by coldness and indifference, and that it is a pity it should have been so. And the person writing, in whatever future epoch he or she may live, will be as mystified by my equivalent in that future time as are those around me now.’

In writing about The book of disquiet, I’ve come to realise that it is next to impossible to sum it up concisely, in any satisfactory, meaningful way. There is too much going on in the Bernardo Soares compartment of Fernando Pessoa’s mind; it would require a book of similar length to the book itself to do it justice. And you would surely only want to read such a book after you have read Pessoa himself, and have had the chance to make up your own mind. Because your book of disquiet will not be my book of disquiet, or indeed, Tim Hopkins’, de Lancastre’s or Jull Costa’s. Any one reader will navigate through its mosaic of thoughts, feelings, ideas and dreams using a different route, and be struck along the way by differing sentences and paragraphs within those fragments. And yet at the end of the book, all those readers who have been beguiled into investing themselves in his sentences will have a strong, perhaps even fraternal sense of Fernando Pessoa; all will have discovered the Bernardo Soares in themselves.